Go in Peace

content warning: death. sickness. pain. loss.

note: In keeping with Korean convention, I use the collective "our" rather than the individual "my". The sentiments expressed here are, nonetheless, entirely mine.

(1)

Our grandfather, Man-Hyong Yoo, died about a week ago, two months after his eightieth birthday.

He had been diagnosed with colon cancer, which, since March, had progressed rapidly from Stage II to Stage IV. On August 11th, he was admitted to surgery. His post-operative condition was nominal at first, but degenerated over the next day. When his kidneys failed and he was no longer breathing independently, my grandmother made the decision to withdraw life support, in accordance with his expressed wishes. He did not suffer, as so many do. He ended a life of eighty years with a few months of terrible sickness, but he died under anesthesia before he had begun to lose his mental facilities, and that was no small mercy.

Family and friends gathered for a funeral on Saturday; he was cremated on Tuesday. I was with my family in Philadelphia until Thursday.

I haven't told many of my friends until now, because I haven't yet figured out what to say. I've made efforts to write, but they haven't been very good. I've been reading a lot, trying to make sense of things, and that helped more. In particular, I've been reading some about the horrors of death in the modern medical system, from those who know more of it than I:

- Who By Very Slow Decay, Scott Alexander

- How Doctors Die, Ken Murray

- I Hope My Father Dies Soon, Scott Adams

- You Can't Save Them All, Miranda Dixon-Luinenburg

...and some philosophy, from some people I respect:

- Yehuda Yudkowsky, 1985–2004, Eliezer Yudkowsky

- The Fable of the Dragon-Tyrant, Nick Bostrom

- The Value of a Life, Nate Soares

- Beyond the Reach of God, Eliezer Yudkowsky, abr. Raymond Arnold

- The Playground and the Gameboard, Alex Altair

I don't know whether I should insist that you go read all of them right now, but they're pretty much the reason that my mind is organized enough to write right now, so there's that.

Though, time helped, too.

My current mental state is "fine". If this post sparks a wave of people sending me condolences, that may well change. If you want to do something to make me happier, I'll get to my only wish later on.

(2)

content warning: poetry. metaphor. transhumanism.

At some point in the past few years -- I honestly can't remember when -- I decided that I didn't want to be so callous when I heard of deaths e.g. on the news. I've decided, with the privileges I've been afforded in life, to use them to save lives -- so maybe I should act more like it? Anyway. My usual exercise for evoking empathy with lives far away from my own goes like this:

I imagine that tomorrow, the entire human race will board an immense spaceship and set sail from this Earth on the greatest adventure of our history. We'll carry with us the last medical discoveries we'll ever need -- the weapons to deny entropy itself its once-thought-inevitable claim to the bodies that are the only known housing for our minds. We'll live far beyond a mere four score years, and in health -- not resigned to a third or a quarter in weakness and decay. We'll turn our human creativity toward finding meaning and purpose and beauty in lives that are not utterly annihilated after two dozen thousand days...and we'll succeed!

We will be immortal, and it will be but the dawn of the human race as we will eventually be known, when we spread across the stars. We will not be beyond the reach of entropy and disaster, but our world will have some guardrails and some padding. Children might burn a finger or lose a toy, but they won't ever be run over by cars. Grandfathers might get sick and need the help of medicine, but we'll give it to them, and they'll live to see their grandchildren become adults. Life will be less...fragile.

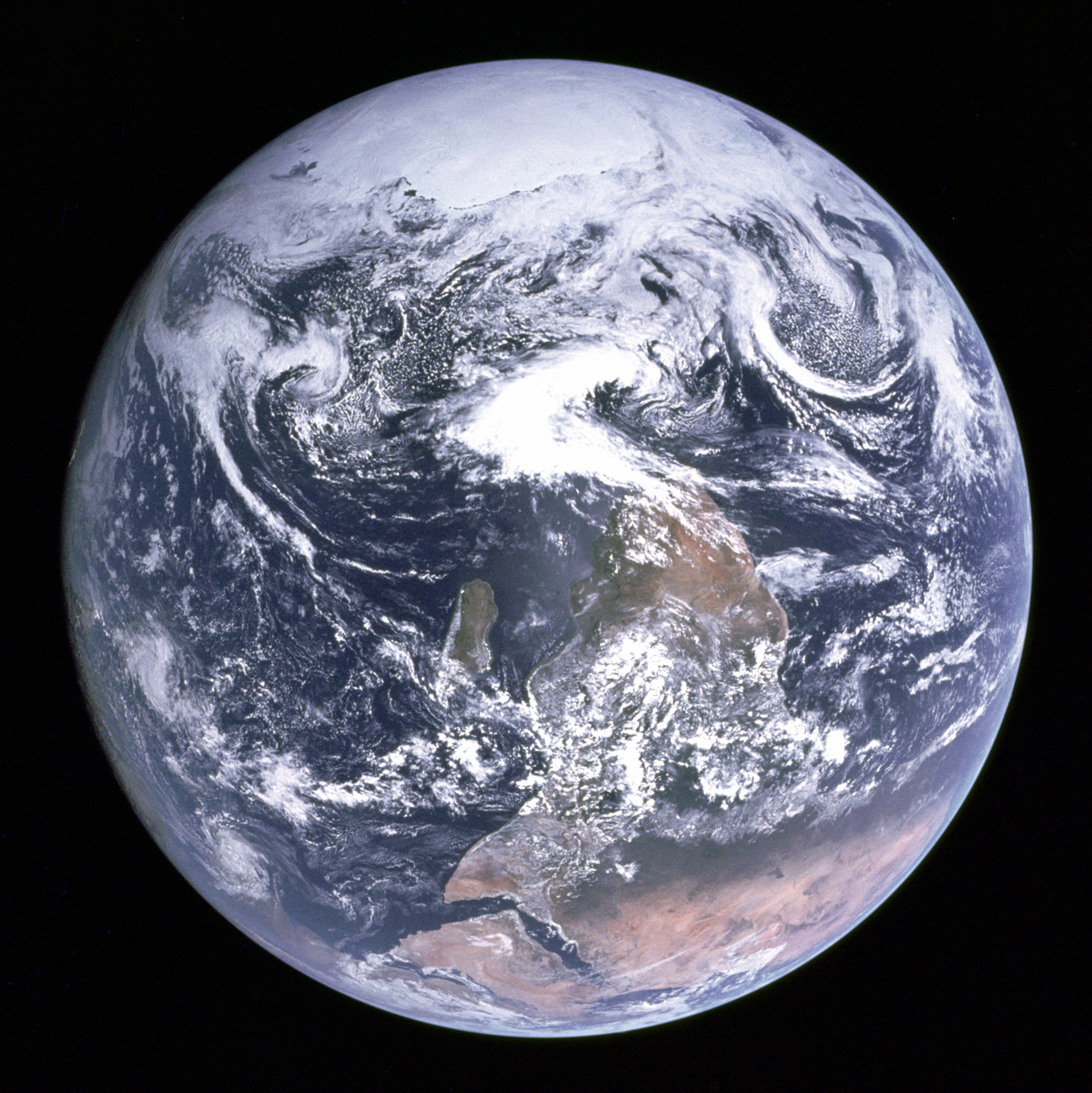

That spaceship, hurtling through space on that day, will look a lot like this:

but will be so different than the world we know. Less sad. Wiser. Kinder. We'll have with us all the greatest minds we have left, and begin to build. Some people speak of killing the dragon-tyrant; I imagine that we'll board a spaceship, at least on the days that I'm trying to understand death.

Because, I guarantee you this:

The day before we get on that ship, the day before we kill the dragon-tyrant, the day before no one has to die forever -- we'll lose someone, completely. And their body won't be frozen, to be awakened when we figure out how -- they'll simply be gone. On that day, this tragedy would not be a-million-a-week, twice-a-second -- we of Earth would have full hours to pause and truly comprehend the tragic news:

We are leaving one behind.

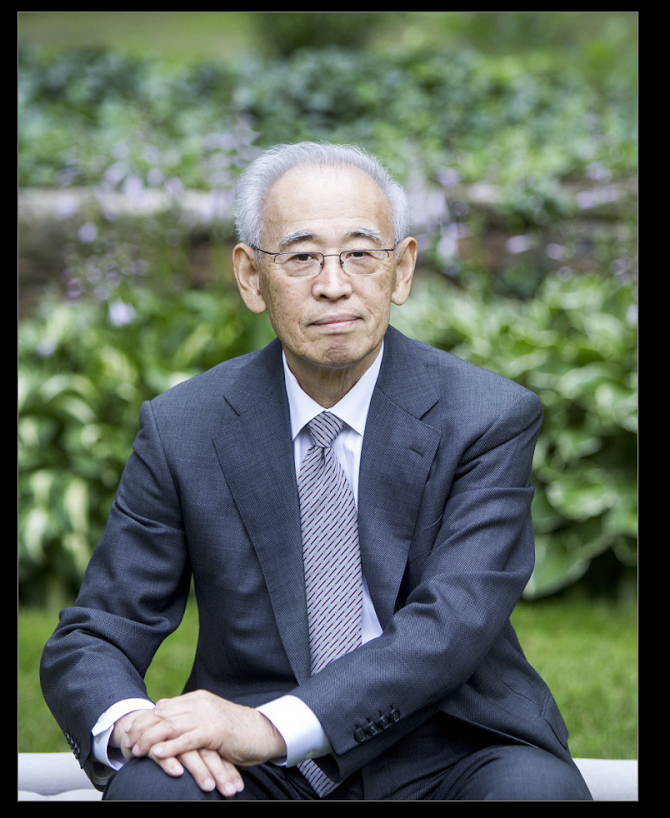

He was a good man. A scientist. A teacher. A father who raised three sons and a grandfather who loved children. He eschewed a life of luxury to ensure that his grandchildren -- all six of them -- had the freedom to chase their dreams.

He did no wrong to the universe, that it chose to destroy him utterly -- but then, the universe is utterly neutral, and does not choose.

He had lived a full life, but was not ready to die. He had stories to tell, he had places to see, and he would have wanted to know his great-grandchildren, whenever they get here.

We leave him behind because we were not strong enough to save him.

We leave him behind because we were not smart enough to know how.

We leave him behind because we did not work fast enough to build the great ship one day sooner.

We are leaving one behind, and we are all poorer for the loss.

Today, if you speak those words in an appropriately solemn tone, we'll leave a hundred behind before you're done. But on that day, we'll have the time. Today, you can't even repeat the first five words fast enough to count the literally incomprehensible masses we're abandoning, but still -- they deserve something. And so, when I hear that a fellow human won't be coming with us, I try to remember to whisper, or maybe just think:

We are leaving one behind.

(3)

Of course, I never dared to hope that I'd have three living grandparents getting on that ship. I wonder, some days, whether I should dare to hope that I will step foot on that ship. Regardless, nothing we can do today will stop the fact that at least a billion present or future humans will be utterly annihilated in everything that makes them them without setting foot on that ship. There was nothing to be done, for nature is utterly neutral in the challenges it sets.

And it is more than enough tragedy for one family to bear this week that we lost a year or five or twenty of a loved father, husband, grandfather, friend. Unlike distant deaths of which we hear only in passing, we have no need to make this death bigger, to use metaphor to explain to our inner monkeys that this was a truly horrible tragedy. We already know.

Except -- why then the story of the ship? Why here, when I already understand the magnitude of this loss? For that matter, why ever in this world where the tools to build the tools to build that ship are only newly in our hands? Why invoke that future day and its nigh-infinite tragedies before we even know that we will make it that far?

Because, as a man I respect repeated when his own brother missed the ship: We must work faster. It may be that you, dear reader, and I, and everyone we each or both hold dear were born too soon to make it onto the ship -- no matter what we do -- and that the aggregate will of humanity could not save one of us from oblivion. It may be that we are all lost, and yet -- someday, if humanity does not kill itself in nuclear misfire or nanotechnological catastrophe or by creating a superintelligence with an imperfect moral directive or by ignoring a sky full of Earth-shattering asteroids or by something new invented by a child born tomorrow -- someday, there may be a boy of a mere twenty-one years who will shed tears, not because he lost a handful of years in which to get to better know his grandfather, but because his grandfather did truly miss the ship, and would not have, had we worked faster.

One death is a tragedy. A million deaths is a catastrophe -- one that happened between the time that our grandfather died and the time that our family gathered to remember him. We must work faster.

This death might have been delayable, but was unpreventable. Our grandfather was born too soon to be saved. But every second we spend working at half-pace is -- in every future in which humanity gets its collective act together -- one human that we leave behind.

We are leaving one behind. It's not our grandfather, but it will be someone's grandfather. And we can allow that, or we can work faster. For me, conflating the two humans missing the boat -- one inevitably and one preventably -- is exactly what my brain needs to understand this, right now. It may not work for you, but it does work for me.

(4)

content warning: strong denunciation of certain religious beliefs.

This was not our grandfather's project; he was a simpler man. (...knowing that better men would come, and greater wars: when each proud fighter brags he wars on Death, for lives...)

But if a childhood of sitting in church services as a skeptic has taught me anything, it taught me to dig through every possible meaning of the minister's words for some hidden true truth wrapped in the gauzy metaphor of religion. And so, when I hear, in the Buddhist service we held,

You are departing for the place of birth, where there is no trace of anything; we believe your death is a promise to return to this world as a new being, stronger in your vow to save sentient beings and reach peace. (translated; slightly paraphrased)

...I wonder if those words could be made to mean something. When you're sitting in the second row of a funeral service listening to a Buddhist priest speak kind and infuriating lies about reincarnation, there's not much else to do.

And so I forged those soft lies into a hard truth:

The conscious mind that was Man-Hyong Yoo does not exist now, just as it did not exist before his birth. That mind is gone, and is never coming back. And the world is poorer for it.

But the causal negentropy that is Man-Hyong Yoo -- all of the things he did or caused to happen -- every act or consequence of his life -- is very much in this world. And the world is richer for it.

It exists in his children. It exists in his grandchildren. In every way that he set out to improve this world, we now have the chance to do better. Not because we are stronger -- but because we are on more solid ground. Because he gave us a tremendous chance.

We will make the world better. We will, each in our own way, bring closer a kinder world, a better world. We will carry our grandfather into that world -- not in spirit, but in the consequences he has left in us. That will be his legacy.

And so I lit a stick of incense and bowed two and a half times before our grandfather's portrait.

(5a)

Our grandfather deserves, as well, to be remembered for who he was, rather than just as an icon in his eldest grandson's grand dreams. His obituary was posted in the Oakridger, and if you've read this far, I'd appreciate it if you'd read it, too:

On the morning of Aug. 12, 2015, Man Hyong Yoo lost his brief battle with colorectal cancer. He was surrounded by family as he succumbed to complications resulting from surgery at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Pa. He was 80 years old.

Man Yoo was born in Seoul, Korea on June 27, 1935. He was the fourth child and third son of Hae Chang Yoo and Chang Kyu Lee. He lived through the challenges of Japanese occupation during World War II and the Korean War (1950-1953), having to provide as man of the house while his father and elder brothers were away.

Graduated from the famous Kyunggi High School in Korea, he traveled to the United States in 1956 to advance his studies, earning multiple degrees from Michigan State University in Lansing, Michigan. He married Sung Ja Choo on Sept. 10, 1960, while a graduate student. After receiving his Ph.D. in Materials Science, he joined the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in 1967 and eventually retired in 2003.

His distinguished career included collaborations and he spent several years living abroad in Germany, Japan and Korea, but always returning home to Tennessee. After retirement, he finally satisfied his itch to teach by joining the faculty at KAIST in Daejon, South Korea and later receiving an appointment to Seoul National University in 2005.

His accomplishments include significant and seminal contributions to the fundamental understanding of plastic deformation, radiation damage and high temperature flow and fracture. His achievements have led the frontier of understanding for both intermetallic materials and hexagonal close-packed metals and alloys. He was the author of more than 180 scientific research papers and numerous book chapters, editor of three books and several conference proceedings, and presenter of more than 50 invited talks.

He received the Humboldt Research Award for Senior U.S. Scientists. He was recognized by his peers at The Minerals, Metals and Materials Society (TMS), which elected him as one of its 100 Living Fellows and conferred on him the Mathewson Gold Medal in 2002.

After retirement, his passion for golf continued, reaching fulfillment when he attended the 2013 Masters. He traveled extensively culminating in conquering Macchu Picchu, Peru in 2014.

He is survived by his wife of 55 years Sung Ja Yoo, three sons, Phillip, Terry (and spouse Penny), and Christopher (and spouse Kris) and six grandchildren, Jennifer, Ross, Sam, Marshall, Duncan, and Brendan.

Of course, if you're ever studying the materials science of aluminum-rich superalloys and encounter "Yoo torque" or the "Yoo effect"...yeah, that was his.

(5b)

He was a great scientist, and he was a good man. With his wife, he raised three sons -- now themselves all good men. He was rich -- because he inherited a small piece of a large fortune and because they used to pay well at Oak Ridge National Labs -- but you couldn't tell, except for the used Lexus he drove and his membership to the local country club, where he golfed.

No, he saved his fortune to fund his grandchildren's education. And I am beyond grateful for it. Today, I am privileged beyond measure to be able to attend the school that I wanted -- and the school that I love -- by the grace of our grandfather's selflessness, generosity, and lifetime of hard work. I am privileged that he was supporting my education and my passions long before I was in college, and if today I ask myself "Do I deserve these things? Why me?", the answer is: our grandfather.

If you have ever met me, then your life was richer for what he gave during his. This is his legacy, though but one small piece.

(5c)

Two last things I wish to remember, which I'll recount here because I don't need to keep them secret, and this is maybe the place they'll be preserved the easiest.

The first is the last words I said to him, before I left for Japan:

Bye, grandpa. I'll come back, and I'll tell you all about it.

The second is that when I walked into his hospital room that Monday, his whole face lit up when he saw me, and he grinned from ear to ear.

There were two things I regret never telling him, and for those, it's too late. I'm not writing them here.

(6)

My family requested that friends refrain from sending flowers, and instead, donate the money they would have spent to the Abramson Cancer Center.

I'm defying their wish, and instead donating, on behalf of our grandfather, to the Machine Intelligence Research Institute, who I believe are -- as the fable tells it -- the ones forging dragon-killing weapons deep underground. Or at least, the ones forging the tools to craft those weapons.

If you join me in donating -- to either cause -- then feel free to let me know; I'll be glad at the news. Other condolences, as I mentioned earlier, are not particularly welcome. I've already spoken with the friends I needed to pull me through this. And now, I've said all that needed to be said.

Except this: