September 5: Bucket o' Links, Back-to-School Edition

Today on Bucket o' Links (sorry, what?), we've got fall classes, textbooks, book-books, Harvard admission statistics, and, of course, Guardians of the Galaxy.

It's shopping week at Harvard. Study cards aren't due until next week, so students have a week free to test-drive classes, skip class entirely, or just mess around.

Wednesday, I was just messing around. Finding myself with no afternoon classes to shop, I instead dropped into the first lecture of Computer Science 50.

CS50 is...well, it's difficult to explain. Any year now, it's going to pass Economics 10 as the largest class at Harvard. It's almost singlehandedly responsible for a tripling in the size of the CS department in the last five years. It's what happens when you give one of the best lecturers in the world a multi-million dollar operating budget and the mission to teach a class, not just for Harvard students, but for anyone in the world who wants to learn. CS50 is an experience. CS50 is what the future of what internet-age education will (or at least should) look like.

The course comes with its own dance-beat-fueled teaser-trailer:

and all of last year's lectures are online for free, if that's a thing you think is cool.

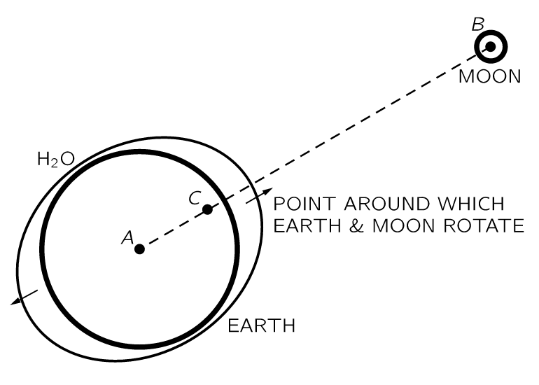

Speaking of legendary lecturers and things online for free, I hadn't realized that The Feynman Lectures on Physics were offered free-to-read online. Speaking as someone who once studied the subject, but gave up when I found more interesting things to do, I still think that figuring out how everything works is really, jaw-droppingly cool, and Dick Feynman is, by all accounts, a wonderful teacher.

Certainly, from what of his I've read, I've found he has a fantastic talent for avoiding many of the convenient lies teachers of physics find it convenient to tell, while nevertheless being able to communicate, elegantly and in plain English, not just the right thing to know, but the right ways to think. (This, incidentally, is a strength he shares with Prof. David Malan, of CS50.)

It's been two years since I took CS50 (or physics, for that matter), and almost that long since I took a seminar course on printing and typography, but I am nevertheless charmed to no end by this essay on margins and why they matter. Excerpt:

Text printed on the best paper with no margins or unbalanced margins is vile. Or, if we’re being empathetic, sad. (For no book begins life aspiring to bad margins.) I know that sounds harsh. But a book with poorly set margins is as useful as a hammer with a one inch handle. Sure, you can pound nails, but it ain’t fun. A book with crass margins will never make a reader comfortable. Such a book feels cramped, claustrophobic. It doesn’t draw you in, certainly doesn’t make you want to spend time with the text.

On the other hand, cheap, rough paper with a beautifully set textblock hanging just so on the page makes those in the know, smile (and those who don’t, feel welcome). It says: We may not have had the money to print on better paper, but man, we give a shit. Giving a shit does not require capital, simply attention and humility and diligence. Giving a shit is the best feeling you can imbue craft with. Giving a shit in book design manifests in many ways, but it manifests perhaps most in the margins.

Speaking of books (okay, we're getting a bit off-track of the "back-to-school" theme; bear with me here), Margaret Atwood has written a book which won't be published until 2114. She's been named as the first contributor to The Future Library project, a 100-year art project which will collect one unpublished work a year from a modern novelist, to all be released in the year 2114. Says Atwood:

"It is the kind of thing you either immediately say yes or no to. You don't think about it for very long," said Atwood, speaking from Copenhagen. "I think it goes right back to that phase of our childhood when we used to bury little things in the backyard, hoping that someone would dig them up, long in the future, and say, 'How interesting, this rusty old piece of tin, this little sack of marbles is. I wonder who put it there?'"

More at The Guardian.

And still speaking of books, but returning once more to campus, I tried to grab tickets for Randall Munroe (of xkcd fame)'s imminent book tour. Predictably, I failed. After all, if there's a city where Munroe could sell out a venue in under five seconds, it's Cambridge, Mass. Anyway, he did an interview on FiveThirtyEight, so that's fun to read. Excerpt:

WH: In “What If?” you often rely on estimation techniques to develop reasonable answers to pretty complex questions. ... Of the estimation techniques you use, which do you think is the most applicable for people to apply to their daily life? What’s a technical takeaway you’d like to see people use more?

RM: ... One thing that’s been really helpful for me is to memorize random quantities to serve as reference points. I remember that Wyoming is the smallest state and has a bit over half a million people, and that New York’s metro area has about 20 million. Boston’s has 5 million, and Tokyo’s has 35 million. “One in 100 Americans” is 3 million people, and “1 in 100 people” is 70 million. Once I have those reference points, when I hear “10 million people have lost power in the storm,” I at least have something to compare it to.

...

But I’m also wary of people saying “everyone should know” some skill from their area of expertise, because people have their own stuff to deal with. It’s easy for me to imagine an abstract person and then say, “Wouldn’t it be better if that person knew how to program?” And maybe it would. But real people are complicated and busy, and don’t need me thinking of them as featureless objects and assigning them homework. Not everyone needs to know calculus, Python or how opinion polling works. Maybe more of them should, but it feels a little condescending to assume I know who those people are. I just do my best to make the stuff I’m talking about interesting; the rest is up to them.

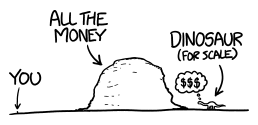

If you aren't already, you should also be reading Munroe's What-If blog; it's definitely the best part about my Tuesday mornings. Excerpt from this week's post, "All the Money":

Also on campus, The Crimson (our school newspaper) recently conducted their annual survey of the incoming freshman class, and has finished a five-part series reporting their results. They are, at times, tragically terrible at reporting statistics, but hey, at least they've got a ton of cool data! (If you care about that sort of thing.) Anyway, here's an interesting tidbit from Part II: Admissions, Financial Aid, and Athletic Recruiting:

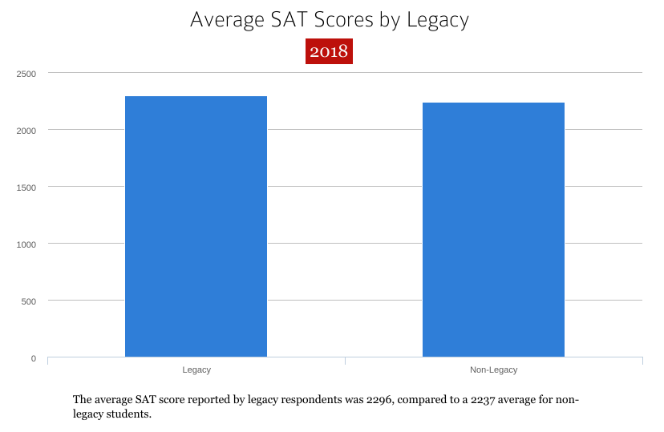

Legacy students on average reported higher test scores than their non-legacy peers. The average SAT for self-reported legacy students was 2296, while the average score for the rest of the survey’s respondents was 2237.

If you take those numbers at face value, it seems as if it's (slightly) harder (on the metric of requiring a higher test score, on average) to be admitted as a legacy applicant.

Which is probably not true. On a Facebook thread, a friend argued rather convincingly that since legacy applicants are disproportionately likely to be white and otherwise socioeconomically advantaged, they are likely to have a harder time being admitted for those reasons (or, conversely, because they're not benefiting from affirmative action and diversity-seeking policies), but that, relative to their non-legacy socioeconomic peers, they do in fact enjoy (some) advantage.

So maybe the world makes sense after all, it just took some digging to find the real (subtle) truth. In technical terms, the observed correlation was caused by a hidden variable, rather than a direct causal relationship; consider it a parable on the dangers of drawing conclusions from sloppy statistics.

...and now for something completely different. This from the tumblrverse:

If you'll bear with me a moment, the curb-cut effect (as explained by Gary Karp), is the idea that, when we do a good thing for one group of people, unexpected benefits may accrue to others:

"What happened when they started cutting the curbs [to accomodate wheelchairs]? Who else benefitted? Bicyclists, parents with strollers, elderly people, delivery people, skateboarders... When you design well for disability, you design well for everyone else. The term isn't 'handicapped design' or 'barrier-free design', it's universal design, good design."

And when this crossed my newsfeed, something clicked: diversity in movies is a social curb-cut. When people who look, or think, or act different than the straight-white-type-A norm are portrayed in positive light, it makes it a little bit easier for people to be different in real life. Even if, as in Guardians, it was completely unintended.

...and that's all! Maybe next week, I'll post something between two successive BoL's. Or not. It'll be a surprise!