[China] Looking Backwards

Challenges in writing about events from the perspective of afterward: Getting things down while they're still fresh in the mind. And so, I figure I'll start with that which is most fresh: returning home.

On the morning of the 23rd, I woke up early enough to see my friends off on their trip to see the Great Wall. I never did get to see it, or the Forbidden City, or the Summer Palace, or the 798 District, or anything else of real cultural interest in Beijing. But that's probably alright; I'll be in China again in the not-so-distant future. It's not like I'm going to see (most of) any of these kids any other time in my life. And so I don't feel so bad about missing a few sightseeing opportunities if it means I got to spend more time with a crop of truly fantastic students.

People ask me "How was China?" or "What did you see?", and my answer to either is "I didn't see much of the country; I only really saw three hundred gifted schoolchildren." Then they say "Oh." and I hastily clarify "But the kids were great, really fantastic." They don't get it, but I really do mean it; they were worth all of the opportunity cost.

My grandfather is fond of saying: "Most things, they can take away. But they can't take away what's in your stomach, or in your head." Which is to say, of course, that when the North Koreans came back to take away your money, they couldn't so easily rob you of what you had invested in your health, or in your education. To that brief list I'll tender a humble addition: "They can't take away what's in your stomach, your head, or your heart."

This was not the first summer camp that changed my life, but it did drive the point home for me: sometimes, experiences change us -- not just what we think, but how we think. When I was writing my lesson plans and running hypothetical contingencies, I was modeling my kids in the reference class "students", not the reference class "people". I planned for them to be receivers of knowledge, just as I would be a (the) distributor of knowledge. For all that I planned to communicate, I didn't plan to dialogue.

I certainly didn't plan to learn. But, at the end of the week, I think my fellow SL summed it up the best, when he said to me, the night before closing ceremonies: (more or less; the errors are entirely mine)

We traveled all this way, to the other side of the world, and found people. Not just humans, but living souls, with personalities, oddities, hopes, faults, and dreams. And so you have to imagine, in this world of seven billion, that there must be so many people.

In my class, we discussed what up-arrow notation meant and the sorts of literally-incomprehensible numbers that it could encode. 3^^^3, for example, is literally impossible to encode in decimal notation -- much less comprehend on an intuitive level -- within our physical universe.

But, even on hyperastronomically smaller scales than that, scope insensitivity is still a very real human failing. It's hard to imagine what a hundred real people means (maybe now I have a better idea, but still not a good one), much less a hundred hundred. Hell, human minds by default have a hard time understanding on a deep level one other mind, much less ten. But to think that there's seventy hundred hundred hundred hundred people...

I have a cached abstract concept that is called "seven billion", but, as I intoned so often in class: "numbers are just names". When I think "seven billion", it doesn't really mean any more to my mental processes than "big number". I can consciously 'know' that it's a big number that happens to be a hundred times as large as "seventy million", but on an intuitive level, I don't grok that number, either. Nor do I know what "seven hundred thousand" or even "seven thousand" mean (the latter maps to "number of students in Harvard College"; but I haven't met any substantive fraction of that group, so I don't actually know how large it is).

I think I 'get' "seventy". That's approximately the number of push-ups I can do, or the number of staff members at HSYLC, or any number of other quantitative comparisons. But I just can't "multiply by a hundred", and I certainly can't do it four times.

Maybe it's impossible. Maybe, if we want to stoke a universal love for our planet, we need a new reference class entirely. We need completely different prototype for understanding "seven billion lives", as "seven billion times a human life" just doesn't work. If your brain can multiply values by quantities, then I am jealous of your clarity. Mine can't. To really understand something truly big, I need to think of it as a new thing, not a multiplication of a few things small.

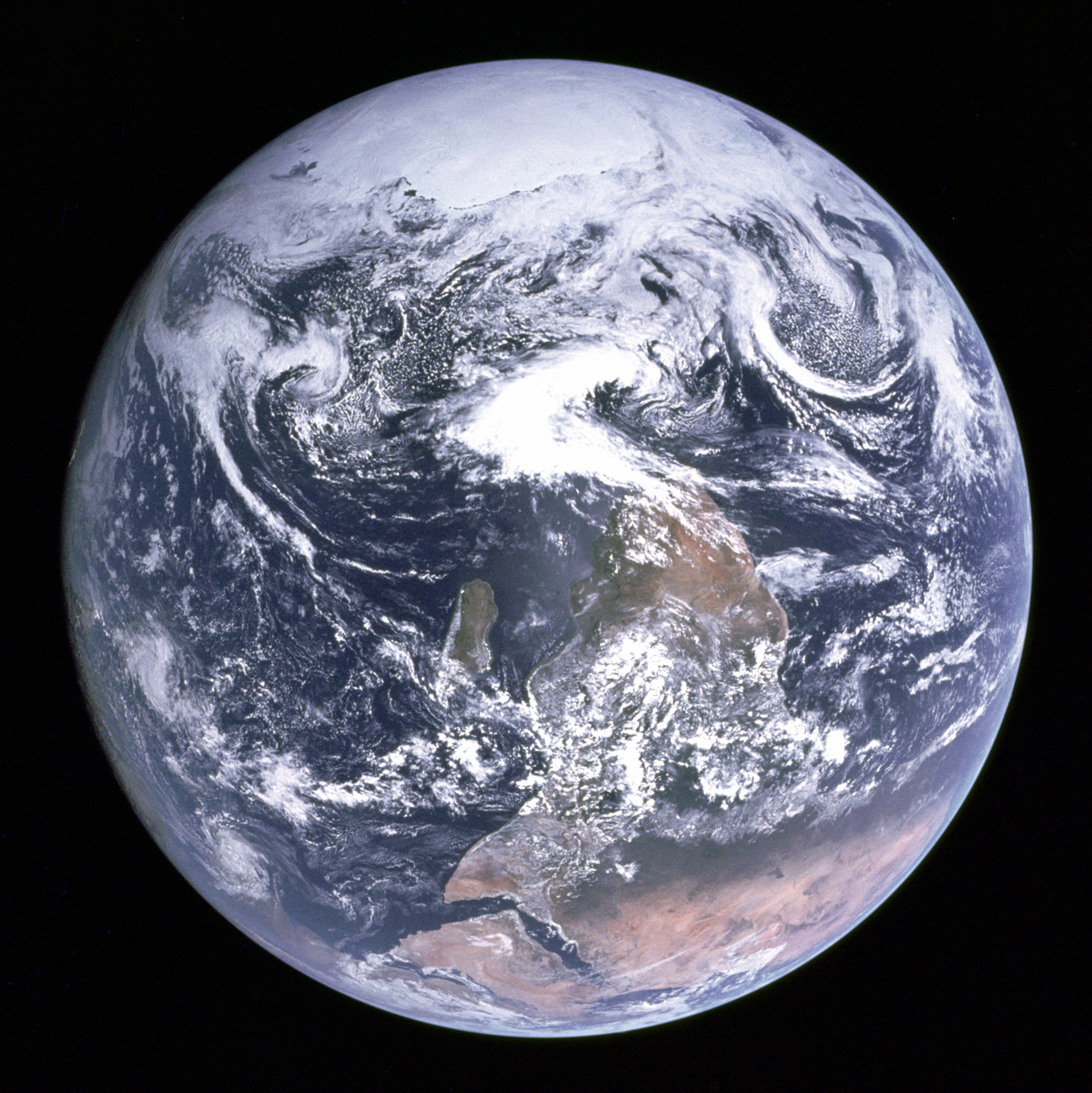

According to Wiki, the 'blue marble' image taken during the 1972 flight of Apollo 17, "was acclaimed by the wide public as a depiction of Earth's frailty, vulnerability, and isolation amid the vast expanse of space."

But for me, I think, I'll try to use this pretty picture as a surrogate for something more meaningful: the love for seven billion individual people-living-lives, on a scale truly unimaginably more vast than the love I'd feel for any one stranger, or even a friend. Because there are lots of people out there, and they're all real people.

If I can learn to love this blue marble seventy hundred hundred hundred hundred times as much as I love a human life, maybe someday more of us can do the same. And if enough of us truly did, maybe we'd see less of pain -- and more of love -- in this world.