Whose Voice? Whose Guide?

nb:The Q Guide is a Harvard-run course rating service. It has its roots in the student-run "Confi Guide", published by the Crimson as far back as 1925. The Confi Guide, however, was eclipsed by the Harvard-run CUE (Committee on Undergraduate Education) reports published from 1975 onwards. In 2005, the "CUE Guide" was renamed the "Q Guide", and moved to an online-only format. Today, the Q website bills itself as "Your Voice, Your Guide".

Much has already been said about the choice to hide important course evaluation data from students (Crimson article), and I won't try to rehash in full what others have said so eloquently. Instead, I'll try to bring to the surface some of the most salient points, and add a few of my own.

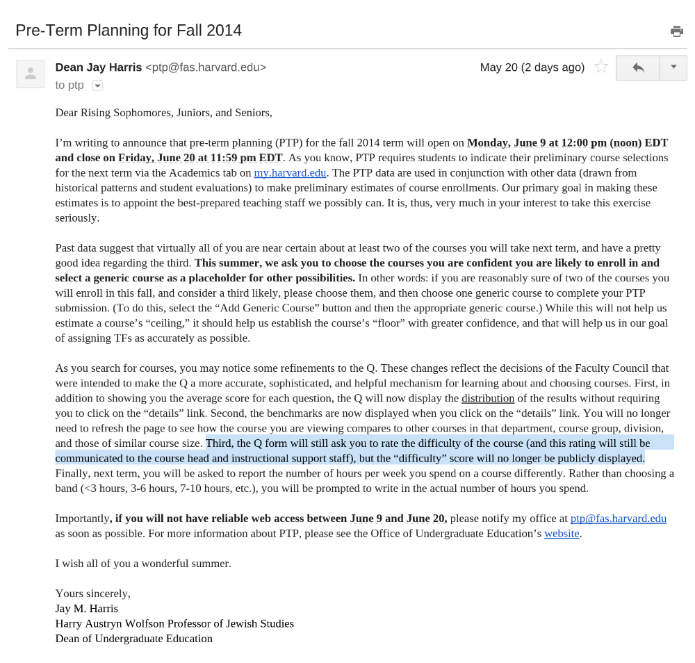

First, it's been said (and satirized by Satire V) that Dean Harris did a fine job of (trying to) bury the lede on the whole matter. After all, the change to the Q was announced in sentence 16 of 21 in an email titled "Pre-Term Planning for Fall 2014":

Now, unless the the Dean was attempting to imply that we should be planning for Fall 2014 by scoping out courses now, before difficulty ratings go away forever, one has to question the reason behind revealing a crucial change in student resources (which, as the Crimson reports, has been decided since last September) in the middle of an email about a weeks-away optional survey to a group of students who have already left campus for the summer.

Or perhaps, one need not. I'm not sure that anyone except University spokespeople would be willing to argue that Dean Harris just happened to send